Therese Neumann

|

|

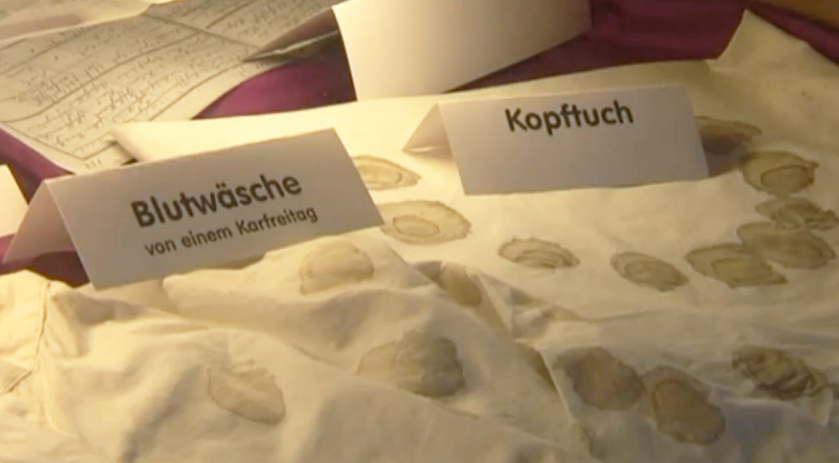

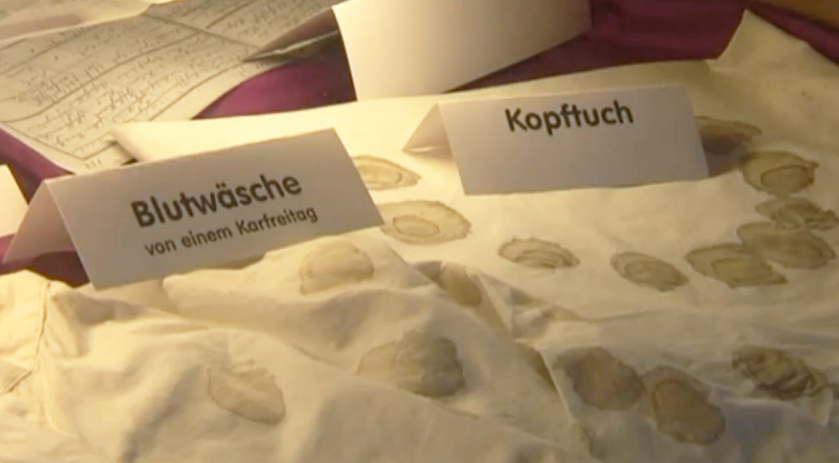

Clothes that were stained with blood from Therese 's stigmata.

Therese Neumann (1898-1962) became the center of worldwide attention in 1926 when, at age 28, she received the stigmata, the manifestation of Christ’s wounds on her body. Soon after, the public also learned of her abstention from all food and drink, except for the daily intake of the Holy Eucharist. Many people saw the stigmata and witnessed Therese’s weekly visions of Christ’s passion and death.

The glorified child Jesus

Therese Neumann was born on Good Friday, April 9, 1898, in Konnersreuth, Bavaria, a remote farming village of 1400 people. The daughter of a tailor and the oldest of ten children, she grew up in a strict, but loving, Catholic home. Therese experienced her first vision of Christ “The glorified child Jesus” at age eleven during her First Communion, but didn’t consider it extraordinary; she thought this was what everyone experienced on this occasion. By 1913, she had decided to become a missionary nun and serve in Africa, but the outbreak of World War I delayed her entry into the convent.

Cheerful and willing

At age 13, to help the family financially, Therese was hired out part-time to a neighboring farm. Her formal schooling ended two years later when her father was drafted into the army, and she was hired out full time. Therese’s cheerful, willing nature was evident even in these early years. She was happiest when there was plenty of work to do and strong enough to do the hardest man’s work. She especially enjoyed working in the fields and with farm animals.

A seven-year ordeal

The morning of March 10, 1918 marked the beginning of a seven-year ordeal for Therese. While fighting a fire on a neighboring farm, she severely injured her back. A few days later, she fell down the cellar steps and hit her head on a concrete floor. When she regained consciousness, her vision was nearly gone. Five months later, Theresa again injured her back and thereafter experienced ongoing headaches and fainting spells that left her unconscious, sometimes for days. By March 1919, a year after the first back injury, Therese was completely blind and paralyzed in both legs.

A willing victim

The role of a helpless invalid was difficult for Therese, as also was giving up her dream of working as a missionary. But with the loving support of her family, she became reconciled to her changed circumstances and devoted herself to prayer and self-offering for the sufferings of others. Though bedridden and in constant pain, Therese never prayed for herself, only for the redemption of souls and that God’s will be done. Her abstinence from solid food dates from this period, when she assumed the throat ailment of a young seminarian.

The intercession of Therese of Lisieux

Therese’s life-long devotion to Therese of Lisieux played an important part in her gradual restoration to health. On April 28,1923, the day Therese of Lisieux was to be “beatified” by the pope, Therese offered up special prayers to the saint, though not to be cured. That same day, she miraculously regained her eyesight. Two years later, on the day the Catholic Church canonized Therese of Lisieux as a saint, Therese was miraculously cured of the paralysis in her legs. While she was silently praying the rosary, a white light suddenly appeared over her bed and a voice said: “Resl (Therese’s nickname) wouldn’t you like to be well again?” Therese answered: Everything is all right with me: living and dying, being well or sick, whatever my dear God wills. He knows what is best…I am happy with all the flowers and birds, or with any other suffering He sends. And what I like most of all is our dear Savior himself. Then the voice said: “Today you may have a little joy. You can sit up; try it once, I’ll help you.” Suddenly, Therese experienced a painful wrenching in her back, as if her spine was being snapped back into place.The voice addressed Therese again: You still have much to suffer, and no doctor can help you, either. Only through suffering can you best work out your desire and your vocation to be a victim, and thereby help the work of the priests. Through suffering you will gain more souls than through the most brilliant sermons. I have already described it before. Father Naber, Therese’s spiritual counselor, later discovered this last statement about suffering in those exact words in Therese of Lisieux’s autobiography.

The stigmata appears

Within a year of being cured of paralysis, the first signs of the stigmata appeared, beginning with the wound above the heart. Therese said: One night, I was busy with my prayers, without being particularly conscious of the passion of Christ, when for the first time, I saw the Savior in the Garden of Olives sweating blood. He looked at me with a loving expression, and at that very moment I felt as if someone had pierced me through the heart with a sharp object, and then withdrawn it. I noticed that blood was flowing, and I felt this stabbing pain in my heart which, with the exception of Easter Week, has never left me completely. Subsequently, on Good Friday, April 13 1926, Therese had her first vision of Christ’s entire passion. Once again, whenever Christ looked at her lovingly, new wounds would appear on her body. Therese received these wounds and those that appeared later as God’s will, sent to propitiate the sins of others and to draw souls closer to the Christ.

Visions of Christ and the disciples

During her weekly visions of the Christ’s passion, Therese experienced the same physical and mental agonies as Christ. The visions occurred every Friday, except for certain holy days, and increased in intensity during Lent, reaching a climax on Good Friday. In her ecstatic state, Therese answered questions that elicited more details about the historical events. Linguists confirmed her accurate use of Aramaic and other foreign languages, unknown to her. Each year, Therese also had as many as a hundred others visions of the lives Christ and his disciples. On August 6, 1926, following a vision of Christ’s transfiguration, Therese experienced no further need of food or drink, and little need for sleep.

The Nazis attempt an arrest

Daily visitors to Therese’s modest family home numbered in the hundreds, while visitors for the Friday visions of Christ’s passion ranged from 5000 to 15,000. The Neumann family refused donations and rejected offers to make films of Therese’s life. The people of Konnersreuth, most of whom saw Therese as a saint, also refused to commercialize Therese’s presence among them. When the Nazis came to power in Germany in 1933, they promptly banned all visitors to Konnersreuth and harassed and threatened Therese. Therese made no secret of her dissenting views and, at the height of Nazi power, boldly predicted Hitler’s downfall. The Nazis made one attempt to arrest Therese, during a Friday vision. As two Gestapo agents approached her home, Therese, at the height of her suffering, suddenly sprang from bed, walked downstairs, and confronted the agents as they reached for the doorbell. The figure of Therese covered with blood, the suffering etched in her face, so awed the two men that they turned and fled.

Endless deeds of charity and kindness

When not experiencing the visions, Therese was constantly busy. At home she cleaned and scrubbed and also worked on the family farm. In the village, she cared for the sick and needy, tended graves in the cemetery, and received guests in the parish house with Father Naber. Her deeds of charity and kindness were endless. It was not unusual for Therese to spend all night arranging flowers for the altars or cleaning the village church. She received prayer requests from all over the world, and served as the instrument for hundreds of miraculous cures. She was particularly sympathetic to would-be suicides and others in despair. During the last years of her life, the Friday visions gradually decreased until they occurred only monthly, on the first Friday. On September 18, 1962, at age 64, Therese died from cardiac arrest.

See/view videos about these events [here] and [here].

|